Izamal

Izamal is an important archaeological site of the Pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is the largest town of the Northern Yucatec lowlands, covering an urban extension of 53 square km. Its monumental buildings exceed 1,000,000 cubic meters of constructive volume and at least two raised causeways, known by their Mayan term sacbeh, connect it with other important centers, Ruins of Ake, located 29 km to the west and Kantunil, 18 km to the south, evidencing the religious, political and economic power of this political unit over a territory of more than 5,000 square kilometres (1,900 sq mi) in extension. Izamal developed a particular constructive technique involving use of megalithic carved blocks, with defined architectonical characteristics like rounded corners, projected mouldings and thatched roofs at superstructures, which also appeared in other important urban centers within its hitherland, such as Ake, Uci and Dzilam. The city was founded during the Late Formative Period (750–200 BC) and was continuously occupied until the Spanish Conquest. The most important constructive activity stage spans between Protoclassic (200 BC – 200 AD) and Late Classic (600–800 AD). It was partially abandoned with the rise of Chichen Itza in the Terminal Classic (800–1000 A.D.) until the end of the Precolumbian era, when Izamal was considered a site of pilgrimages in the region, rivaled only by Chichen Itza. Its principal temples were sacred to the creator deity Itzamna and to the Sun god Kinich Ahau.

Five huge Pre-Columbian structures are still easily visible at Izamal (and two from some distance away in all directions). The first is a great pyramid to the Maya Sun god, Kinich Kak Moo (makaw of the solar fire face) with a base covering over 2 acres (8,000 m²) of ground and a volume of some 700,000 cubic meters. Atop this grand base is a pyramid of ten levels. To the south-east lies another great temple, called Itzamatul, and placed at the south of what was a main plaza, another huge building, called Ppap Hol Chak, was partially destroyed with the construction of a Franciscan temple during the 16th century. The south-west side of the plaza is partially limited by another pyramid, the Hun Pik Tok, and in the west lie the remains of the temple known as Kabul, where a great stucco mask still existed on one side as recently as the 1840s, and a drawing of it by Frederich Cahterwood (see our earlier article on his drawings and works) was published by John Lloyd Stephens. All these large man-made mounds probably were built up over several centuries and originally supported city palaces and temples. Other important residential buildings which have been restored and can be visited are Xtul (The Rabbit), Habuc and Chaltun Ha.

Spanish Colonial era

After the Spanish conquest of Yucatan in the 16th century a Spanish colonial city was founded atop the existing Maya one; however it was decided that it would take a prohibitively large amount of work to level these two huge structures and so the Spanish contented themselves with placing a small Catholic temple atop the great pyramid and building a large Franciscan monastery atop the acropolis. It was named after San Antonio de Padua. Completed in 1561, the open atrium of the Monastery is still today second in size only to that of Saint Peter in the Vatican. Most of the cut stone from the Pre-Columbian city was reused to build the Spanish churches, monastery, and surrounding buildings.

Izamal was the first chair of the Bischop of the Yucatan before it was relocated to Merida. The fourth Bishop of Yucatán, Fray Diego de Landa lived here.

For a day trip to Izamal look at our Homun and Izamal day trip section.

Yaxcaba

It is believed that the original settlement at Yaxcaba was established by the survivors of the fall of Mayapan in 1441.

In colonial times under the encomienda system it was administered by Joachim of Leguizano (1562) and Andres Valdés.

Architecture

In the municipality seat Yaxcabá, there is St. Francis of Assisi church, the chapel dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe, all dating from the colonial era. There is also the Santa Cruz church, former convent and parish of St. Peter and St. Nicholas Chapel.

Yaxuna is a Mayan archaeological site, also in the municipality of Yaxcaba in central Yucatan.

The settlement had a long continuous occupation running from the Middle Formative Period through the Postclassic. The Late Formative saw the construction of a number of triadic architectural groups linked with roads running north to south. Some of the larger pyramids were remodeled during the Early Classic, and held royal tombs. In the Late Classic (ca. 600–800), the city-state of Coba conquered Yaxuna and built a 100 km Sacbe, or raised road, to connect the two cities. This was the longest the Maya ever built. Internally, new roads running east to west were constructed. In the Terminal Classic (800–1100), the state of Chichen Itza to the north began a war with the Coba state, and Yaxuna constructed a city wall, but Chichén Itzá appears to have conquered the city by around 950. Sacked and ritually destroyed, the city never recovered. By the Postclassic (1100–1697), the population was much reduced, with new construction limited to minor additions to older architecture.

Calakmul

Calakmul is located in Campeche state in southeastern Mexico, about 35 km north of the border with Guatemala and 38 km north of the ruins of El Mirador. It is located on a rise above a large seasonal swamp lying to the west, known as the El Laberinto bajo (denoting a low-lying area of seasonal marshland). The swamp was an important source of water during the rainy season. The bajo was linked to a sophisticated water-control system including both natural and artificial features such as gullies and canals that encircled a 22-square-kilometre (8.5 sq mi) area around the site core, an area considered as Inner Calakmul. The location of Calakmul at the edge of a bajo provided two additional advantages: the fertile soils along the edge of the swamp and access to abundant flint nodules. The city is situated on a promontory formed by a natural 35 m high limestone dome rising above the surrounding lowlands. This dome was artificially levelled by the Maya. During the Preclassic and Classic periods settlement was concentrated along the edge of the El Laberinto bajo, during the Classic period structures were also built on high ground and small islands in the swamp where flint was worked.

Calakmul was a major Maya power within the northern Petén region of the Yucatán of southern Mexico. Calakmul administered a large domain marked by the extensive distribution of their emblem glyph of the snake head sign, to be read “Kaan”. Calakmul was the seat of what has been dubbed the Kingdom of the Snake or Snake Kingdom. This Snake Kingdom reigned during most of the Classic period. Calakmul itself is estimated to have had a population of 50,000 people and had governance, at times, over places as far away as 150 km. There are 6,750 ancient structures identified at Calakmul; the largest of which is the great pyramid at the site. Structure 2 is over 45 m high, making it one of the tallest of the Maya pyramids. Four tombs have been located within the pyramid. Like many temples or pyramids within Mesoamerica the pyramid at Calakmul increased in size by building upon the existing temple to reach its current size. The size of the central monumental architecture is approximately 2 km2 and the whole of the site, mostly covered with dense residential structures, is about 20 km2.

Throughout the Classic Period, Calakmul maintained an intense rivalry with the major city of Tikal to the south, and the political maneuverings of these two cities have been likened to a struggle between two Maya superpowers.

Calakmul vs. Tikal

The history of the Maya Classic period is dominated by the rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul, likened to a struggle between two Maya “superpowers”. Earlier times tended to be dominated by a single larger city and by the Early Classic Tikal was moving into this position after the dominance of El Mirador in the Late Preclassic and Nakbe in the Middle Preclassic. However Calakmul was a rival city with equivalent resources that challenged the supremacy of Tikal and engaged in a strategy of surrounding it with its own network of allies. From the second half of the 6th century AD through to the late 7th century Calakmul gained the upper hand although it failed to extinguish Tikal’s power completely and Tikal was able to turn the tables on its great rival in a decisive battle that took place in AD 695. Half a century later Tikal was able to gain major victories over Calakmul’s most important allies. Eventually both cities succumbed to the spreading Classic Maya collapse.

The great rivalry between these two cities may have been based on more than competition for resources. Their dynastic histories reveal different origins and the intense competition between the two powers may have had an ideological grounding. Calakmul’s dynasty seems ultimately derived from the great Preclassic city of El Mirador while the dynasty of Tikal was profoundly affected by the intervention of the distant central Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacan.[25] With few exceptions, Tikal’s monuments and those of its allies place great emphasis upon single male rulers while the monuments of Calakmul and its allies gave greater prominence to the female line and often the joint rule of king and queen.

Collapse

In 751 Ruler Z erected a stelae that was never finished, paired with another with the portrait of a queen. A hieroglyphic stairway mentions someone called B’olon K’awiil at about the same time. B’olon K’awiil was king by 771 when he raised two stelae and he was mentioned at Toniná in 789. Sites to the north of Calakmul showed a reduction in its influence at this time, with new architectural styles influenced by sites further north in the Yucatán Peninsula.

A monument was raised in 790 although the name of the ruler responsible is not preserved. Two more were raised in 800 and three in 810. No monument was erected to commemorate the important Bak’tun-ending of 830 and it is probable that political authority had already collapsed at this time. Important cities such as Oxpemul, Nadzcaan and La Muñeca that were Calakmul’s vassals at one time now erected their own monuments, where before they had raised very few; some continued producing new monuments until as late as 889.[63] This was a process that paralleled events at Tikal. However, there is strong evidence of an elite presence at the city continuing until AD 900, possibly even later.

In 849, Calakmul was mentioned at Seibal where a ruler named as Chan Pet attended the K’atun-ending ceremony; his name may also be recorded on a broken ceramic at Calakmul itself. However, it is unlikely that Calakmul still existed as a state in any meaningful way at this late date. A final flurry of activity took place at the end of the 9th century or the beginning of the 10th. A new stelae was erected, although the date records only the day, not the full date. The recorded day may fall either in 899 or 909 with the latter date the most likely. A few monuments appear to be even later although their style is crude, representing the efforts of a remnant population to maintain the Classic Maya tradition. Even the inscriptions on these late monuments are meaningless imitations of writing.

Ceramics dating to the Terminal Classic period are uncommon outside of the site core, suggesting that the population of the city was concentrated in the city centre in the final phase of Calakmul’s occupation. The majority of the surviving population probably consisted of commoners who had occupied the elite architecture of the site core but the continued erection of stelae into the early 10th century and the presence of high status imported goods such as metal, obsidian, jade and shell, indicate a continued occupation by royalty until the final abandonment of the city. The Yucatec-speaking Kejache Maya who lived in the region at the time of Spanish contact in the early 16th century may have been the descendants of the inhabitants of Calakmul.

NASA technology aiding archaeologists

Spotting ancient Maya ruins — a challenge even on the ground — has been virtually impossible from the sky, where the dense Central American rainforest canopy hides all but a few majestic relics of this mysterious civilization. Now, NASA archaeologist Dr. Tom Sever and scientist Daniel Irwin of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., and archaeologist Dr. William Saturno of the University of New Hampshire in Durham are using advanced, space-based imaging technology to uncover the ruins. High-resolution satellite imaging, which detects variations in the color of plant life around the ruins, can pinpoint sites of Maya settlements from space. The research, primarily conducted at the National Space Science and Technology Center in Huntsville and the University of New Hampshire, is made possible by a partnership between NASA and the Guatemalan Institute of Anthropology and History. (NASA/T. Sever)

NASA, university scientists uncover lost Maya ruins — from space

by Steve Roy and Erika Mantz

Remains of the ancient Maya culture, mysteriously destroyed at the height of its reign in the ninth century, have been hidden in the rainforests of Central America for more than 1,000 years. Now, NASA and university scientists are using space- and aircraft-based “remote-sensing” technology to uncover those ruins, using the chemical signature of the civilization’s ancient building materials.

NASA archaeologist Tom Sever and scientist Dan Irwin, both from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, are teaming with William Saturno, an archaeologist at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, to locate the ruins of the ancient culture.

“From the air, everything but the tops of very few surviving pyramids are hidden by the tree canopy,” said Sever, widely recognized for two decades as a pioneer in the use of aerospace remote-sensing for archaeology. “On the ground, the 60- to 100-foot trees and dense undergrowth can obscure objects as close as 10 feet away. Explorers can stumble right through an ancient city that once housed thousands — and never even realize it.”

Sever has explored the capacity of remote sensing technology and the science of collecting information about the Earth’s surface using aerial or space-based photography to serve archeology. He and Irwin provided Saturno with high-resolution commercial satellite images of the rainforest, and collected data from NASA’s Airborne Synthetic Aperture Radar, an instrument flown aboard a high-altitude weather plane, capable of penetrating clouds, snow and forest canopies.

These resulting Earth observations have helped the team survey an uncharted region around San Bartolo, Guatemala. They discovered a correlation between the color and reflectivity of the vegetation seen in the images — their “signature,” which is captured by instruments measuring light in the visible and near-infrared spectrums — and the location of known archaeological sites

In 2004, the team ground-tested the data. Hiking deep into the jungle to locations guided by the satellite images, they uncovered a series of Maya settlements exactly where the technology had predicted they would be found. Integrating cutting-edge remote sensing technology as a vital research tool enabled the scientists to expand their study of the jungle.

The cause of the floral discoloration discerned in the imagery quickly became clear to the team. The Maya built their cities and towns with excavated limestone and lime plasters. As these structures crumbled, the lack of moisture and nutritional elements inside the ruins kept some plant species at bay, while others were discolored or killed off altogether as disintegrating plaster changed the chemical content of the soil around each structure.

“Over the centuries, the changes became dramatic,” Saturno said. “This pattern of small details, impossible to see from the forest floor or low-altitude planes, turned out to be a virtual roadmap to ancient Maya sites when seen from space.”

Under a NASA Space Act Agreement with the University of New Hampshire, the science team will visit Guatemala annually through 2009, with the support of the Guatemalan Institute of Anthropology and History and the Department of Pre-Hispanic Monuments. The team will verify their research and continue refining their remote sensing tools to more easily lead explorers to other ancient ruins and conduct Earth science research in the region.

“Studies such as these do more than fulfill our curiosity about the past,” Sever said. “They help us prepare for our own future

Scientists believe the Maya fell prey to a number of cataclysmic environmental problems, including deforestation and drought, that led to their downfall, Irwin said. “The world continues to battle the devastating effects of drought today, from the arid plains of Africa to the southern United States,” he said. “The more we know about the plight of the Maya, the better our chances of avoiding something similar.”

Another aspect of the research involved using climate models to determine the effects of Maya-driven deforestation on ancient Mesoamerican climate. The goal of this effort was to determine whether deforestation can lead to droughts and if the activities of the ancient Maya drove the environmental changes that undermined their civilization.

Extending benefits of remote-sensing technologies is part of NASA’s Earth-Sun System Division. NASA is conducting a long-term research effort to learn how natural and human-induced changes affect the global environment, and to provide critical benefits to society today.

Sever and Irwin conduct research at National Space Science and Technology Center in Huntsville, a joint science venture between NASA’s Marshall Center, Alabama universities, industry and federal agencies. For more information about its work, visit http://www.nsstc.org/.

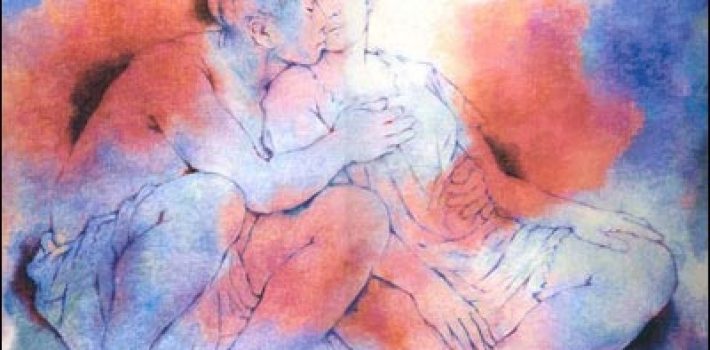

Fernando Castro Pacheco – Yucatecan artist

Fernando Castro Pacheco (January 26, 1918 – ) is a Mexican painter, engraver, illustrator, print maker and teacher. As well as being known for traditional artistic forms, Castro Pacheco illustrated several children’s books and produced works in sculpture. He is more popularly known for his murals that invoke the spirit and history of the Mexican people. His works evoke a unique use of color and form.

Education and early career

Born in Mérida, Yucatán in Mexico, Castro Pacheco went on to become a well known international and local artist. Little has been published about the artist’s early life. While some scholars insist that he was a mostly self-taught artist, Castro Pacheco began his “formal” training at the Mérida School of Fine Arts at the age of 15.”[1] While at the school, he honed his artistic skills in engraving and painting. During the time he spent at his school, he studied under the instruction of Italian artist Alfonso Cardone. It was at this school that he completed his first engravings in both wood and linoleum. Castro Pacheco spent six years at the school and produced many works during this early period in his artistic career. He also worked as an instructor and taught painting and drawing in the Mérida area.

Upon completion of his studies, Castro Pacheco is credited with co-founding La Escuela Libre de Las Artes Plásticas de Yucatán in 1941. He also served as an instructor for the school. This school, like many others founded during this period, moved the art classroom and studio into an outdoor atmosphere, allowing the artist to more freely capture the beauty, color and realism of nature in art. The idea of outdoor schools of art was promoted by Alfredo Ramos Martinéz. The idea centered on the promotion of more liberal methods for art instruction. In 1942, soon after the founding of the school, Castro Pacheco produced his first lithographs and displayed his painting and drawings in his first exhibit at the Galería de la Universidad de Yucatán.

While in Mérida, Castro Pacheco began work on several murals around the city. Between 1941 and 1942, he completed murals in the preschools (jardines de niños) or playgrounds in Mérida, as well as in several rural school buildings including the Escuela Campesina de Tocoh located in the rural henequen-producing area near Mérida. He also completed al fresco murals with cultural and sport themes at the Biblioteca de la Union de Camioneros de Yucatán in Mérida.

Career in Mexico City

In 1943 Castro Pacheco moved to Mexico City where his career and personal life took new directions. Castro Pacheco married during this time and fathered two children. Relating to his career in art, it was during his time in Mexico that he was first linked to the Taller de Gráfica Popular. The Taller was a group of artists and printmakers that formed in 1937 most likely from the dissolved Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios(League of revolutionary writers and artists) or LEAR which had been active in Mexico City prior to suffering from internal problems. The Taller is associated with popular political movements in Mexico during this time that included “progressive democratic” ideas and support for union workers and people of the lower classes. Castro Pacheco’s role at the Taller is debated. According to some sources he was a somewhat important artist at the Taller, producing engravings and prints that exemplified the face of the poor and suffering in Mexico. According to other sources Castro Pacheco’s role at the Taller was brief and limited, only participating in one show with the group upon his arrival in Mexico City. It was through this first exhibit with the Taller however, that Castro Pacheco gained attention as a print maker and artist. A portfolio of his work was included at the exhibition which gained him attention in the Mexico City art scene and in the international scene as well. Castro Pacheco continued as a print maker until 1960. Working first with linoleum and then between 1945 and 1960 with predominantly wood cuts.

First International Exhibits

After his arrival and success in Mexico City, Castro Pacheco exhibited his works on an international level. In 1945 a selection of his paintings were exhibited the United States at a gallery in San Francisco, California. In 1947 his paintings were part of a collective exhibition in Havana, Cuba.

Later Career and International Study

Upon his return to Mexico City, in 1949 he was named a professor of the Escuela National de Artes Plásticas. Castro Pacheco continued to produce works in various medium while in Mexico City. Moving away from tradition canvas, he is credited with producing the scenery for the ballet productions Guernica and La nube estéril at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City in 1953. Remaining a prominent and active artist, in 1963 Castro Pacheco earned a commission from the Institución Nacional de Bellas Artes to travel to countries including Spain, Italy, France, England, the Netherlands and Belgium in order to study the artistic styles of these countries.

Sisal

Sisal is a seaport town in the municipality of Hunucmá in the state of Yucatán, Mexico. It was the main port of Yucatán during the henequen boom, later overshadowed when the more modern port of Progreso was built to the east. It lent its name to the agave-derived sisal fiber (or hemp) which was shipped through it. In the old days when the hemp was shipped out of Sisal, the packs of the natural fiber were stamped with the word “Sisal” so that port authorities at the country of entry (mainly the US) knew that the merchandize was shipped for this port. However, the name Sisal was used instead to name hemp itself, thus it became Sisal in the US market. In Mexico the fiber is known as henequen, not hemp.

The town is about 53 km north north-west of Mérida, the state capital. By law when the Yucatán was part of New Spain, all commerce went through the port of Campeche. The residents of Mérida petitioned for a port closer to the capital, and this was granted by Spanish royal decree on 13 February 1810. The new port of Sisal was founded in 1811, and has a late colonial era fortress, the “Castle of Sisal”, and an old lighthouse. After Yucatán’s independence from Spain commerce in the port grew rapidly, and by 1845 was shipping cargos with twice the value that had previously gone through Campeche.

After the development of Progreso, Sisal’s importance declined and today is a small fishing village, visited by some for its beach.As of the Mexican census of 2010, Sisal had an official population of 1,837 inhabitants. Currently (Dec 2006) the state government is working to return this port to the splendor of centuries past through the development of projects focused on tourism. The port is planned to grow into a tourist destination as well as shelterport for fishermen.During your visit to Celestun include a stop at Sisal. It is definitely off the beaten path, offering very peaceful beaches, few tourists and the charm you can expect from a small and sleepy town along the Yucatecan coast.

Edzna

Edzna is a Mayan archaeological site in the north of Campeche on the Yucatan peninsula (Gulf coast).

The most remarkable building at the plaza is the main temple. Built on a platform 40 m high, it provides a wide overview of the surroundings. Another significant building located in the plaza is a ball court. Two parallel structures make up the ball court. The top rooms of the ball court were possibly used to store images of the gods associated with the events, along with items needed for the games.

Edzná was already inhabited in 400 BC, and it was abandoned circa 1500 AD. During the time of occupation, a government was set up whose power was legitimized by the relationship between governors and the deities. In the Late Classic period Edzná was part of the Calakmul polity. Edzná may have been inhabited as early as 600 BC but it took until 200 AD before it developed into a major city. The word Edzná comes from “House of the Itzás” which may suggest that the city was influenced by the family Itzá long before they founded Chichen Itzá. The architectural style of this site shows signs of the Puuc style, even though it is far from the Puuc Hills sites. The decline and eventual abandonment of Edzná still remains a mystery today.

The archaeological site of Edzna has been known to local people since time immemorial. Even though the state government was aware of the existence of the ruins in 1906, it was not until 1927, when Nazario Quintana Bello, Inspector of Monuments, gave them the name of Edzná.

A year later, Federico Mariscal presented the first drawings and plans and Enrique Juan Palacios and Morley deciphered several stelae.

The most important restoration in Edzná was convened under the patronage of the INAH, between 1970 and 1976, by Ramón Piña Chan. The last works (1994-1997), were led by Antonio Benavides, with Guatemalan laborers and masons from the Quetzal-Edzná refugee camp, under the patronage of the European Union.

The surprising system of dams and canals were built to store and distribute water. Located at the bottom of a valley, Edzná used to flood in the rainy season. As a solution to the problem, they built a complex network of canals used to transport goods and people and to defend them from outside attack.

The name Edzná, “House of the Itzá”, comes from the Itzá, a lineage of Chontal origin. The Itzá were a Mayan patronymic that extended to various groups of native Putun and Chontal Indians in south-eastern Campeche. Other translations have also been suggested: “House of the Eco” or “House of the Gestures”, in reference to the stucco mask thought to exist in the crest of the tallest building in the area.

Founded around 400 B.C., its peak was reached during the late Classic period. A gradual decline began in the year 1000, leading to its eventual abandonment in 1450.

In its golden age, it appears that it was home to 25,000 inhabitants, distributed in an approximate area of 26 square kilometers. The city had numerous religious, administrative, and residential buildings, which were built in the three architectural Mayan styles of the area: Puuc, Petén, and Chenes.

San Felipe

Rio Lagartos is one of those sites that deserve a very good look but is mostly off the radar for most visitors. The likely reason it is still a well kept secret is that the reserve is not near a large city or airport. Both Cancun and Merida are more than 2.5 hours away. In order to enjoy an unhurried visit, it is best to allocate an overnight stay, which may deter some visitors. However, even if it is a bit hurried for a one day trip, it should be high on your list if you truly enjoy wild life. The flamingo boat ride is the thing to do when you are visiting Rio Lagartos for one day. If you have more time, the crocodile night tour and the bird watching tour are excellent choices. San Felipe is the nearest town to the Rio Lagartos reserve, where simple but clean lodging is available.

The town of San Felipe and Rio Lagartos lie approximately 42 km north of Tizimin. Mérida is located 250 km southwest. Río Lagartos is located at a lagoon, the Ria Lagartos, which is part of a natural reserve. This makes it an ideal place for bird watching. This lagoon is part of the Petenes mangroves ecoregion, and the Ria Lagartos has been designated as an internationally recognized Important Bird Area (IBA). In terms or size of the flamingo community, Rio Lagartos is possibly more important than Celestún, although the latter is significantly closer to Merida and that is the reason most people seeking the flamingos opt for Celestún.

Paseo de Montejo

Paseo de Montejo, Colonial Splendor in Merida

Merida’s elegant tree-lined Paseo de Montejo is the city’s main boulevard and most fashionable district. Once a primarily residential area, the Paseo de Montejo in Merida has since been commercialized and many of the historic 19th century mansions that line the boulevard have been converted into restaurants, nightclubs, boutique hotels, shops, office buildings and museums.

Located northeast of the central plaza and architecturally reminiscent of Havana, Cuba, the area surrounding the Paseo de Montejo in Merida was developed during the henequen boom of the late 19th and early 20th century as plantation owners looking to move out of the city’s historic center built gorgeous mansions along this stretch of boulevard.

The Paseo de Montejo is home to Merida’s Monumento a la Bandera (Flag Monument) and the former Museo Regional de Antropologia (Regional Anthropology Museum) which used to be housed at the Palacio Canton, one of the grandest mansions along the boulevard.

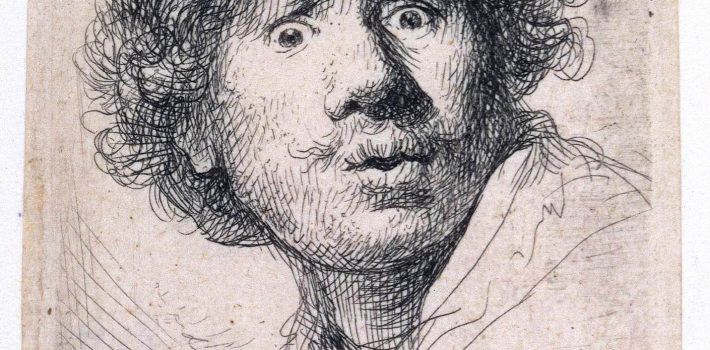

Rembrandt in Merida

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, the Dutch painter and etcher was born 406 years ago. The collection exhibited at El Olimpo is part of the Milán – Madrid – Mexico City – Merida tour. The Rembrandts will remain in Merida until October 20th. The title of the exhibit is “Rembrandt: Lo divino y lo humano”, (“Rembrandt: the divine and the human”).

Since this exhibit consists exclusively of etchings, the following information regarding the artists refers primarily to this technique.

Rembrandt produced etchings for most of his career, from 1626 to 1660, when he was forced to sell his printing-press and virtually abandoned etching. Only the troubled year of 1649 produced no dated work. He took easily to etching and, though he also learned to use a burin and partly engraved many plates, the freedom of etching technique was fundamental to his work. He was very closely involved in the whole process of printmaking, and must have printed at least early examples of his etchings himself. At first he used a style based on drawing, but soon moved to one based on painting, using a mass of lines and numerous bitings with the acid to achieve different strengths of line. Towards the end of the 1630s, he reacted against this manner and moved to a simpler style, with fewer bitings. He worked on the so-called Hundred Guilder Print in stages throughout the 1640s, and it was the “critical work in the middle of his career”, from which his final etching style began to emerge. Although the print only survives in two states, the first very rare, evidence of much reworking can be seen underneath the final print and many drawings survive for elements of it.

In the mature works of the 1650s, Rembrandt was more ready to improvise on the plate and large prints typically survive in several states, up to eleven, often radically changed. He now uses hatching to create his dark areas, which often take up much of the plate. He also experimented with the effects of printing on different kinds of paper, including Japanese paper, which he used frequently, and on vellum. He began to use “surface tone,” leaving a thin film of ink on parts of the plate instead of wiping it completely clean to print each impression. He made more use of drypoint, exploiting, especially in landscapes, the rich fuzzy burr that this technique gives to the first few impressions.

His prints have similar subjects to his paintings, although the twenty-seven self-portraits are relatively more common, and portraits of other people less so. There are forty-six landscapes, mostly small, which largely set the course for the graphic treatment of landscape until the end of the 19th century. One third of his etchings are of religious subjects, many treated with a homely simplicity, whilst others are his most monumental prints. A few erotic, or just obscene, compositions have no equivalent in his paintings. He owned, until forced to sell it, a magnificent collection of prints by other artists, and many borrowings and influences in his work can be traced to artists as diverse as Mantegna, Raphael, Hercules Segers, and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.

Recent Comments